Describing Ourselves as Physicists

Overview

Identity in physics can be challenging to find. We’re given a narrow set of labels to choose from, typically theorist or experimentalist, and these can often be time-dependent as we progress in our careers. Throughout my time in the discipline, I’ve worked in experimental labs, theory groups, and more applied settings. Many times I’ve branded myself a theorist, perhaps more out of desire than measure; however, I’ve always wanted a more nuanced way of describing my work, myself, and my developmental stage. Here, I’ve gathered and visualized thoughts on the topic from various sources. Short answer: like most things, it depends on a clever choice of coordinates.

Categories by Approach to Physics

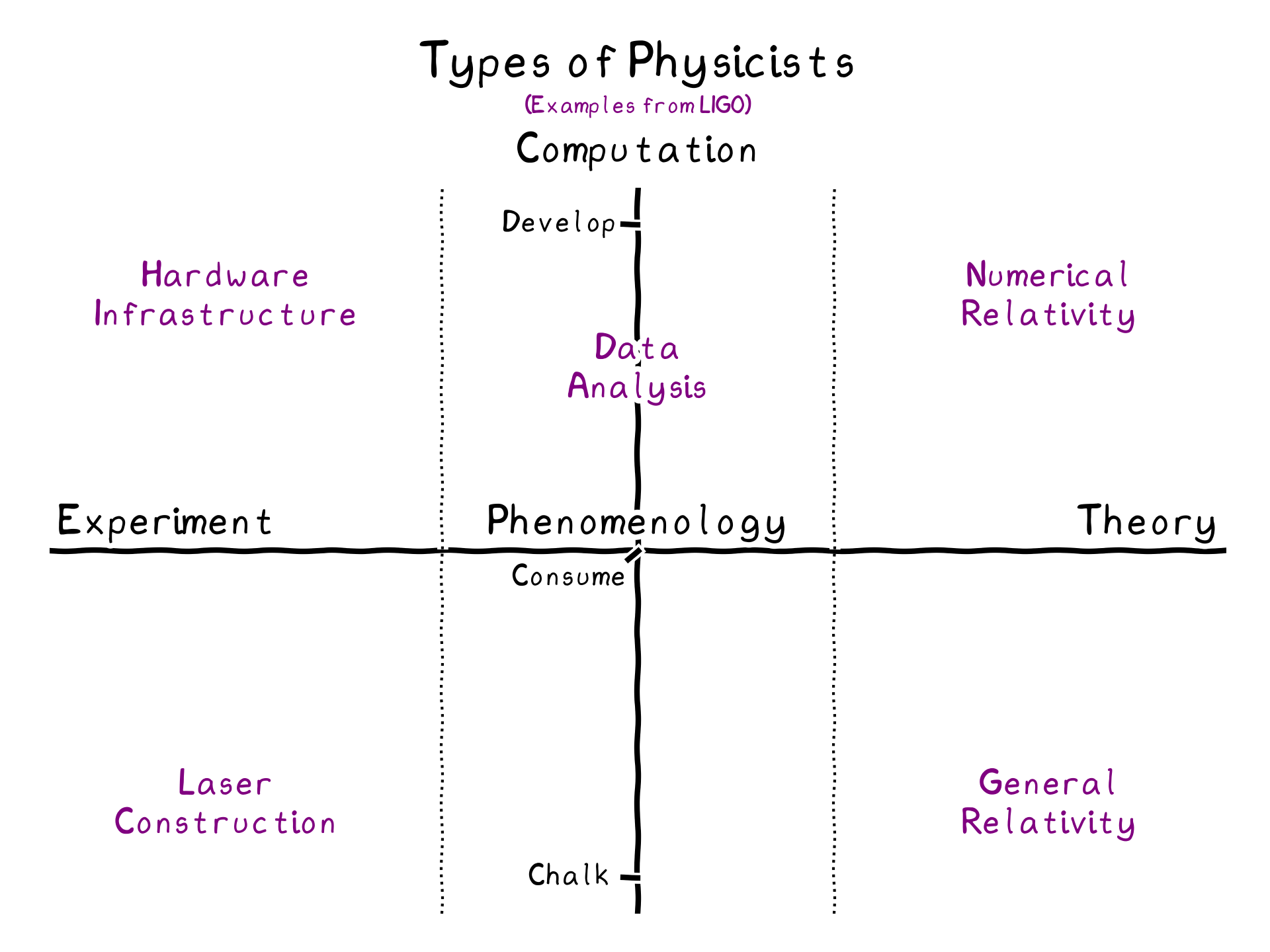

As physicists we are taught, ab-initio, the distinction between experimental physics and theoretical physics. Where theory seeks answers to fundamental questions about the principles of nature, experiment aims to precisely test existing theories and apply them to practical domains. In doing so, experiment often uncovers new phenomena, which gives theorists a new supply of challenges to tackle.

What this description offers in brevity, it lacks in nuance, especially in an era of increasing sophistication of experiment. The gulf between theory and experiment, created by growing specialization and size of experiment, has allowed more room for phenomenology, or the application of theory to experimental outcomes (often in the form of data). While the distinctions are usually fuzzy in practice, they are often used as absolute descriptors; you can be an experimentalist, or a theorist - that’s it. It’s time that this excluded middle be included as a first-class citizen in the landscape of physics disciplines.

In conversation, phenomenology is often muddied with software development. “Isn’t phenomenology is just data analysis?” It can be, but it can also be other things. For these reasons, I find it more clear to conceptualize technological sophistication as a separate dimension. Each discipline of experiment, phenomenology, and theory can range from analog methods to advanced programming in practice. The diagram above takes these thoughts into consideration, and includes examples from the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

Categories by Approach to Thought

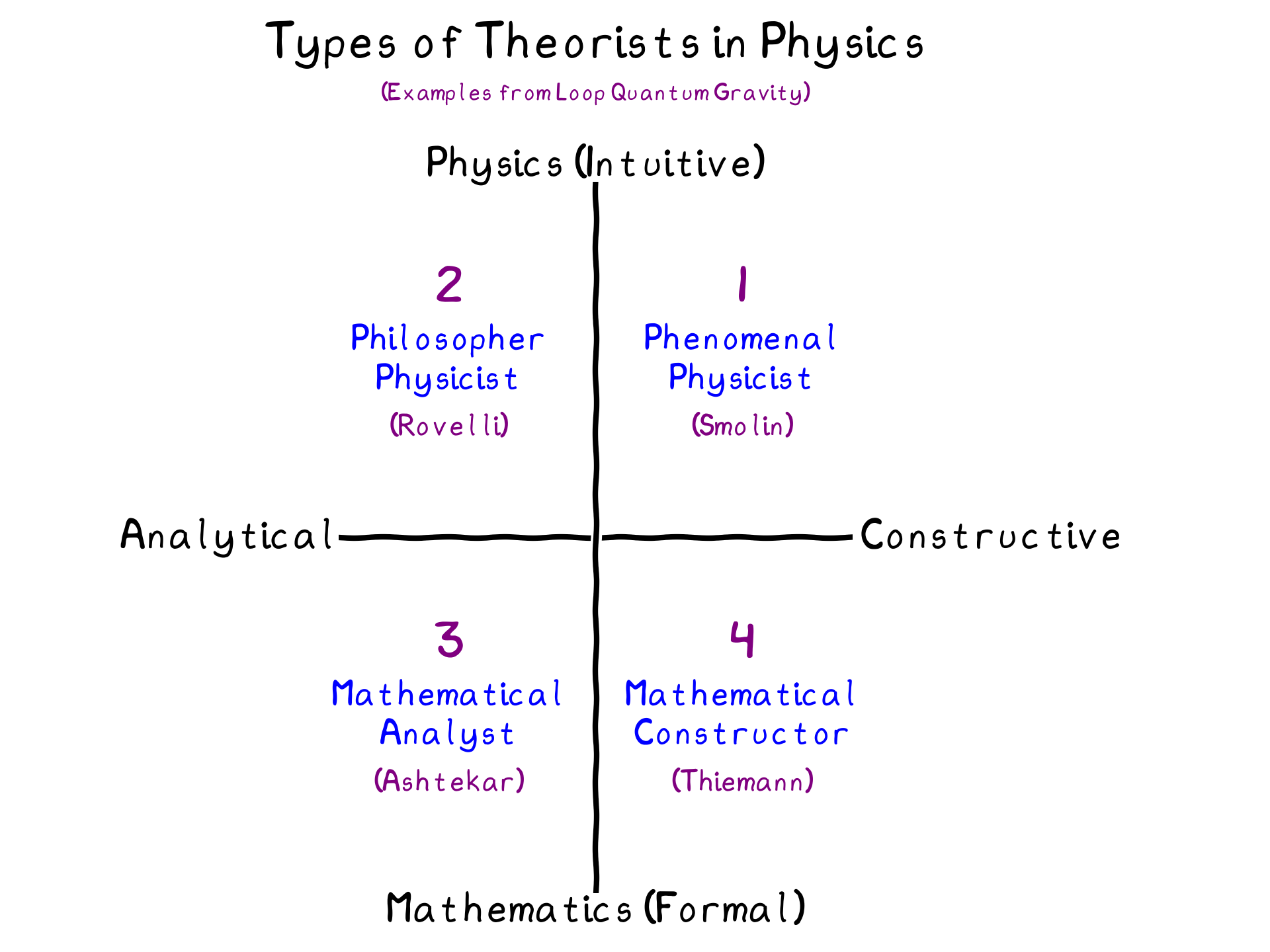

While these categories focus primarily on approaches within theory, I find they apply more broadly to all physicists, since we all encounter theory almost somewhere. This classification is adapted from Martin Bojowald’s popular science book Once Before Time, and uses two dimensions: mathematical v. physical, and analytical v. constructive. The former refers to the preference of tools, formal or intuitive, respectively. The latter refers to the preference of objective, dissecting exiting ideas or conjecturing new ones.

The above contains four key examples, which I detail below. Those with knowledge of the development of Loop Quantum Gravity will appreciate the sample theorists included above. To anyone else interested in these historical anecdotes, see 1.

Phenomenal Physicist. The adrenaline enthusiast guided solely by intuition and concerned only with physical function, a phenomenal physicist wanders through nature in long, powerful strides. By virtue, they are more often wrong than right, and relish the label “crazy.” Consequently, they can usher in radical leaps in models of the universe, but must also be constrained by all the other types of theorist.

Philosopher Physicist. Ever focused on deep physical concepts, the philosopher physicist prides themselves on the artistry of intuitive reasoning. Often seen quoting poetry or literature, they seek the foundational meaning of ontology and epistemology in physics, and therefore can tend to be both profoundly insightful and impractical.

Mathematical Analyst. Often misunderstood as nitpicking, the mathematical analyst is a meticulous tool-bearer who can’t readily accept a physical theory until all the mathematical details have been sorted. At their humble best, they can advance and crystallize laws underlying existing physical theory. However, at worst, they may take known results, refurbish, and resell them as new findings.

Mathematical Constructor. A tinkerer of symbolic expressions, the mathematical constructor loves to build and study new classes of formal objects in the hope of advancing theory. Capable of enduring long and tedious progress, they can indulge in tremendously convoluted detail; however, this can often produce mathematically-fruitful detours on which the relation to physics is lost.

Categories by Career Development Stage

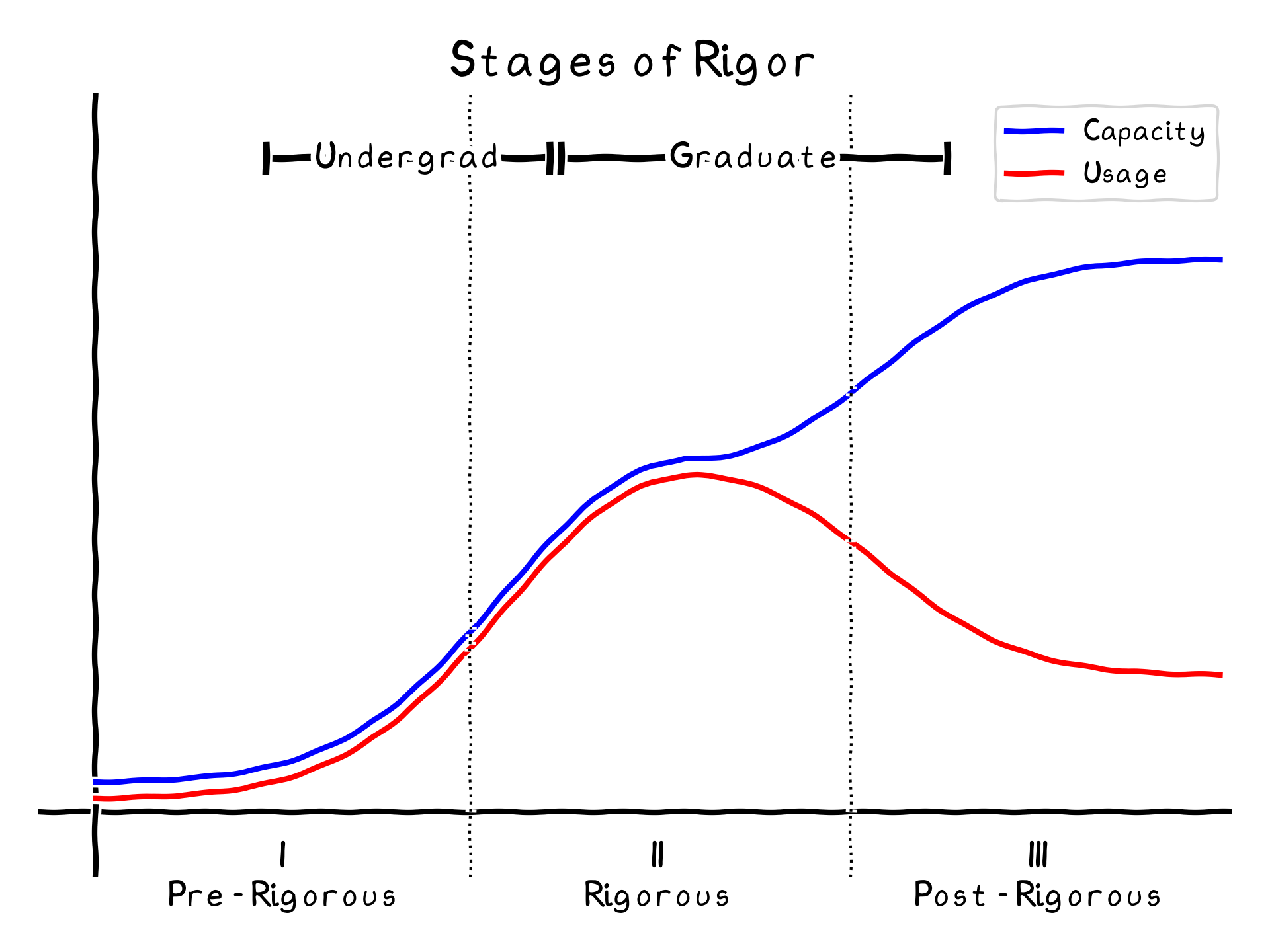

As we are wont to do as physicists, we have first established a kinematic picture, and now want to stir in some dynamics. While the trajectory of my career might look like a particle in a box in the above two categorizations, this next classification seems more one-size-fits-all. Put forth by the eminent Terry Tao, this system describes the usage and reliance upon mathematical rigor throughout the career of a mathematician. I find that it aptly describes the usage of mathematics in physics as well, particularly for theorists.

The classification above has three stages: pre-rigorous, rigorous, and post-rigorous, which we describe below. For the original piece by Tao, see 2.

Stage I: Pre-Rigorous. Wave those hands, and sweep those details under the rug. This stage is all about “shut up and calculate,” with priority being given to ability to complete computations over understanding of the underlying mechanics. Relying heavily on examples (think, harmonic oscillator!), this stage can lean on intuition and coarse, fuzzy concepts. If you’ve found yourself pioneering interpretive dance moves during an exam while using the right-hand rule, you’ve been here. Tao suggests this stage lasts until the early undergraduate years for mathematicians (perhaps slightly longer for physicists).

Stage II: Rigorous. Rewind the tape, it’s time to check the fundamentals. This stage is primarily concerned with doing things the “proper” way, and often involves revisiting previously learned material in considerably increased depth. In mathematics, this can mean a focus on formal and symbolic precision as well as rebuilding known results with deeper understanding of method, not necessarily of meaning. In physics, we also revisit old topics with new mathematical tools; however, we also partially prioritize the meaning of physical principles and how they apply to given settings. Tao suggests this stage lasts from late undergraduate to early graduate years.

Stage III: Post-Rigorous. Settle in and let the tea steep. This stage is focused on the continual refinement of intuition, based on a fully-rigorous understanding of the foundations. For example, quickly performing simplified calculations in GR by using symmetries, then being able to go back and fully expand the detail if required. The focus here is now on field-specific applications of theory, intuitive exploration of research topics, and the “big-picture” contextualizing and shaping how specific research fits within physical frameworks. Tao suggests this stage lasts from late graduate years and beyond.

One particular point of Tao’s that I appreciate as a physicist doing mathematics, is that rigor is not meant to destroy intuition, but rather to correct, clarify, and elevate it. For more on the implications of rigor, see 2.

Conclusion: Self-Classification

While the search for ideal coordinates never ends, the above three systems have at least given me more terms to describe my work, myself, and my career. As of the time of this writing, and if all axes are bounded on $[0, 1]$ in the first two systems, I have approximate coordinates (0.8, 0.8) in the first system, (0.2, -0.8) in the second, and (2.9) in the third.

Thanks to Joshua Black, Cort Posnansky, Matthew Krebs, Chad Hanna, Martin Bojowald, and Garrett Wendel for their helpful discussion and consideration of these topics over many conversations.

References

M. Bojowald, Once before Time: A Whole Story of the Universe, 1. Vintage Book ed (Vintage Books, New York, NY, 2010). ↩︎

There’s More to Mathematics than Rigour and Proofs | What’s New, https://terrytao.wordpress.com/career-advice/theres-more-to-mathematics-than-rigour-and-proofs/. ↩︎ ↩︎